Ten firms produce identical products at average and marginal cost of ten dollars. They agree to sell for twelve dollars. The agreement is a contract in restraint of trade not enforceable in the courts, at least in Anglo-American legal systems. Will it hold?

It might occur to the owner of one of the firms that, while selling a thousand units a day at a profit of two dollars a unit is very nice, selling two thousand a day at a profit of a dollar ninety would be even nicer. Such chiseling might eventually bring down the cartel byt, if he does not do, it one of the others might, eliminating the cartel with no initial windfall to him.

How attractive that idea is, hence how unstable the cartel is, depends in part on how quickly the other firms cut their prices in response. If discovering what he is doing, deciding how to react, revising their price lists, getting the retailers to change their ads, takes a month, the first mover makes about $54,000 extra profit before they do it. If it takes them only a day, he makes only $1800. If it only takes them ten minutes …

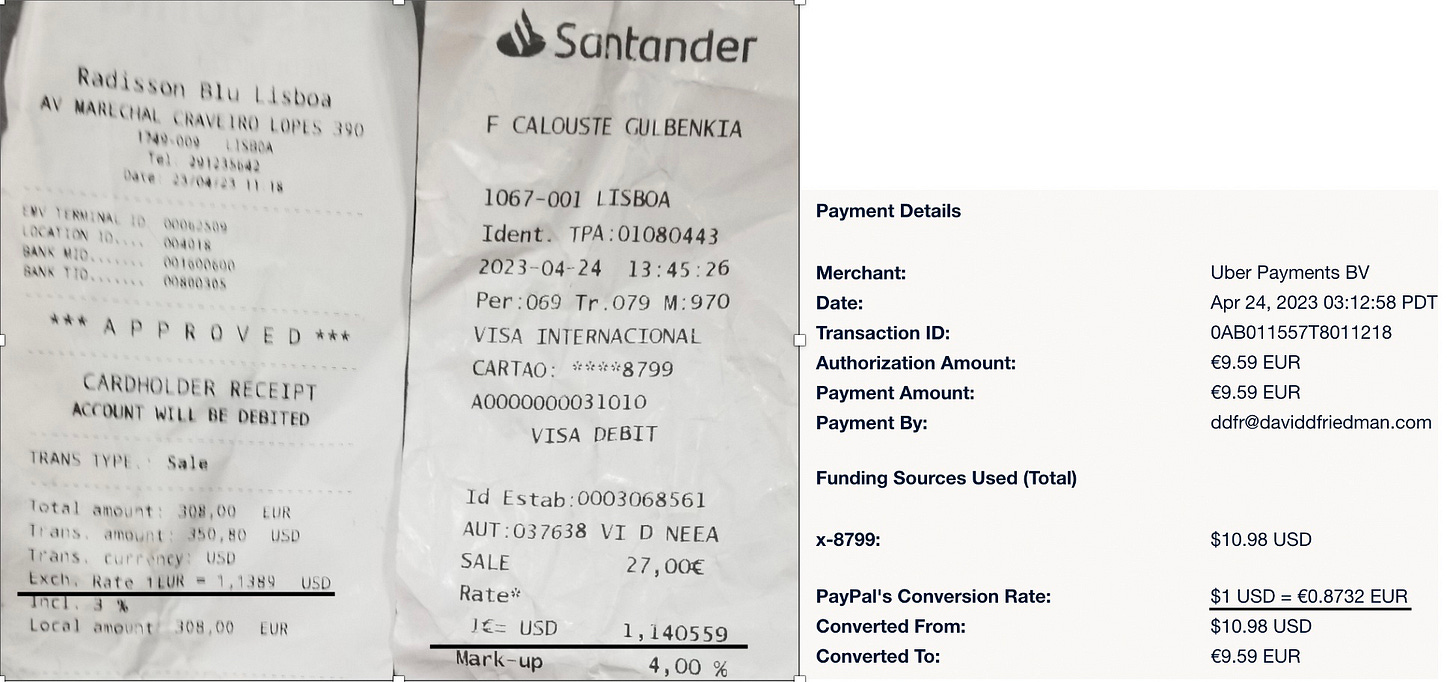

What started me thinking about the question was observing the rates at which I could convert dollars to Euros in Lisbon. Looking up the exchange rate online, one Euro was worth $1.10. When I tried to get Euros from an airport ATM it was charging me something close to $1.30 per Euro — I did not know then that I was going to write this post so didn’t record the number. When I got to my hotel, the hotel offered me 80 Euros for 100 dollars, a rate of $1.25/Euro. I wanted some cash for the short term, so took the offer.

Checking several ATM’s I found that I could not get a rate significantly better than what the hotel was offering. Banks have transaction costs, so I did not expect to exchange at 1.1 to 1, but a surcharge of fifteen dollars on a hundred struck me as higher than what I have observed for similar transactions in the past. That started me thinking about cartel pricing and under what circumstances it would or would not work.

A bank can, I presume does, change the exchange rate in its ATM’s or the rate it offers hotels and other businesses almost instantly as market rates change. It should not be hard to have an employee check what rates other banks are offering every hour or two by looking at their ATM’s. If a bank starts charging less than fifteen percent for its services responding should take hours, not weeks or months. So although I would normally expect competition among banks to drive the exchange rate they offered down to the market rate plus transaction costs, it might not.

I have not checked my memory of past currency conversion rates against evidence, so it is possible that I am mistaken and the current charges are normal. I have no special expertise in cartel or oligopoly theory so it is possible, even likely, that my recent insight on the connection between the speed with which competitors can respond to price changes and the stability of cartels is something someone else thought up a century ago, something routinely covered in textbooks. But whether or not it is original, I think the argument is correct.

Aside from explaining my recent experiences trying to convert dollars into Euros, the argument may have more general implications. Communication has gotten faster over time. Computers respond to changed circumstances faster than humans. So one effect of technological change may be to make it easier for firms to collude.

Or maybe not. The same changes that make it easier for sellers to react to what other sellers do make it easier for buyers as well. The chiseler’s advantage may not last as long as it did in the past but more buyers than before may spot the lower price and switch.

One way to gain customers by covertly undercuting a cartel price is to give discounts to special customers — ones who can be trusted not to tell too many people about the deal they are getting. The railroads did it with rebates. I expect that if I had arrived in Lisbon with a lot of dollars that I wanted to convert, I might have been able to manage a special deal.

Modern encryption and online payments, ideally in digital cash sufficiently secure to make transactions invisible to third parties, could make it easier to cut prices for some, perhaps many, customers while maintaining the illusion of selling at the cartel price. If so, the development of computer technologies may make cartels less rather than more stable.

How to Get a Better Exchange Rate

I am spending less than a week in Lisbon, did not bring a large quantity of dollars and do not need a large quantity of Euros. I have, however, been getting a rate for at least some of my transactions better than that offered by my hotel or the ATMs — by making transactions with my debit card and having the conversion done somewhere far from Lisbon, possibly by my bank. Any readers who know more about the relevant machinery are welcome to fill in the blanks in my knowledge.

When I paid the hotel (Radisson Blu — the breakfast buffet is extraordinary) for two more nights, the cost was 308 Euros, converted into $350.80, a rate of $1.14/Euro. When I bought tickets for the Gulbankian, possibly the most impressive private museum in the world, the exchange rate was about the same. If I take a cab I pay in Euros but if I take an Uber not only do I not need any cash, the charge, paid from my bank account, is converted at 1:1.145

If you are traveling and don’t have a better way than I do of converting your money, do as few transactions as possible with currency.

I am now in London. The ATM's give about $1.50/pound, when the official exchange rate is $1.25/pound. I decided to try cash instead of Visa, got 80 pounds for $100, which is very close to the official exchange rate.

Information costs for buyers are very high. A tourist has limited time and doesn't want to spend it shopping for better exchange rates (or walking blocks to another bank or ATM). So overcharging loses very little business.