Central to the discussion of the economics of war in The Wealth of Nations is the distinction between an army of amateurs, a militia, and a professional army.

In a society of hunters, farmers, or shepherds (nomads such as the Mongols or, earlier, Scythians) the ordinary activities of life provide an adequate substitute for military training:

The ordinary life, the ordinary exercises of a Tartar or Arab, prepare him sufficiently for war. Running, wrestling, cudgel-playing, throwing the javelin, drawing the bow, etc., are the common pastimes of those who live in the open air, and are all of them the images of war.

…

They who live by agriculture generally pass the whole day in the open air, exposed to all the inclemencies of the seasons. The hardiness of their ordinary life prepares them for the fatigues of war, to some of which their necessary occupations bear a great analogy. The necessary occupation of a ditcher prepares him to work in the trenches, and to fortify a camp as well as to enclose a field. The ordinary pastimes of such husbandmen are the same as those of shepherds, and are in the same manner the images of war. (Quotes are from The Wealth of Nations, Book 5, Chapter 1, Part 1 “Of the Expense of Defence”)

Once the crops are planted, a nation of farmers can use the whole male population to invade their neighbors:

All the men of the military age, however, may take the field, and, in small nations of this kind, have frequently done so. In every nation the men of the military age are supposed to amount to about a fourth or a fifth part of the whole body of the people. If the campaign, should begin after seed-time, and end before harvest, both the husbandman and his principal labourers can be spared from the farm without much loss. He trusts that the work which must be done in the meantime can be well enough executed by the old men, the women, and the children. He is not unwilling, therefore, to serve without pay during a short campaign, and it frequently costs the sovereign or commonwealth as little to maintain him in the field as to prepare him for it. The citizens of all the different states of ancient Greece seem to have served in this manner till after the second Persian war; and the people of Peloponnesus till after the Peloponnesian war.

A militia works less well for a civilized nation with a high level of division of labor since the activities of its citizens are less suited as training for war and less seasonal:

Though a husbandman should be employed in an expedition, provided it begins after seed-time and ends before harvest, the interruption of his business will not always occasion any considerable diminution of his revenue. Without the intervention of his labour, nature does herself the greater part of the work which remains to be done. But the moment that an artificer, a smith, a carpenter, or a weaver, for example, quits his workhouse, the sole source of his revenue is completely dried up. Nature does nothing for him, he does all for himself. When he takes the field, therefore, in defence of the public, as he has no revenue to maintain himself, he must necessarily be maintained by the public. But in a country of which a great part of the inhabitants are artificers and manufacturers, a great part of the people who go to war must be drawn from those classes, and must therefore be maintained by the public as long as they are employed in its service.

Further:

When the art of war, too, has gradually grown up to be a very intricate and complicated science, when the event of war ceases to be determined, as in the first ages of society, by a single irregular skirmish or battle, but when the contest is generally spun out through several different campaigns, each of which lasts during the greater part of the year, it becomes universally necessary that the public should maintain those who serve the public in war, at least while they are employed in that service. Whatever in time of peace might be the ordinary occupation of those who go to war, so very tedious and expensive a service would otherwise be far too heavy a burden upon them.

It follows that:

In these circumstances there seem to be but two methods by which the state can make any tolerable provision for the public defence.

It may either, first, by means of a very rigorous police, and in spite of the whole bent of the interest, genius, and inclinations of the people, enforce the practice of military exercises, and oblige either all the citizens of the military age, or a certain number of them, to join in some measure the trade of a soldier to whatever other trade or profession they may happen to carry on.

Or, secondly, by maintaining and employing a certain number of citizens in the constant practice of military exercises, it may render the trade of a soldier a particular trade, separate and distinct from all others.

If the state has recourse to the first of those two expedients, its military force is said to consist in a militia; if to the second, it is said to consist in a standing army. The practice of military exercises is the sole or principal occupation of the soldiers of a standing army, and the maintenance or pay which the state affords them is the principal and ordinary fund of their subsistence. The practice of military exercises is only the occasional occupation of the soldiers of a militia, and they derive the principal and ordinary fund of their subsistence from some other occupation. In a militia, the character of the labourer, artificer, or tradesman, predominates over that of the soldier; in a standing army, that of the soldier predominates over every other character: and in this distinction seems to consist the essential difference between those two different species of military force.

…

When a civilised nation depends for its defence upon a militia, it is at all times exposed to be conquered by any barbarous nation which happens to be in its neighbourhood. The frequent conquests of all the civilised countries in Asia by the Tartars sufficiently demonstrates the natural superiority which the militia of a barbarous has over that of a civilised nation. A well-regulated standing army is superior to every militia. Such an army, as it can best be maintained by an opulent and civilised nation, so it can alone defend such a nation against the invasion of a poor and barbarous neighbour. It is only by means of a standing army, therefore, that the civilization of any country can be perpetuated, or even preserved for any considerable time.

The shift from primitive to modern military technology — what a modern economist would describe as a shift from labor intensive to capital intensive1 — changes the balance between civilized and barbarous nations:

In modern war the great expense of firearms gives an evident advantage to the nation which can best afford that expense, and consequently to an opulent and civilised over a poor and barbarous nation. In ancient times the opulent and civilised found it difficult to defend themselves against the poor and barbarous nations. In modern times the poor and barbarous find it difficult to defend themselves against the opulent and civilised. The invention of firearms, an invention which at first sight appears to be so pernicious, is certainly favourable both to the permanency and to the extension of civilization.

The Ukraine War

Smith was writing in the 18th century but the argument is still relevant. Russia has more than three times the population of Ukraine which, in a war whose results depended on manpower, should be an overwhelming advantage. But the NATO countries, while unwilling to contribute troops, are providing tanks, ammunition, artillery and money, and the combined GNP of the NATO nations and Ukraine is about twenty times the GNP of Russia. That gives Ukraine a large advantage in capital intensive warfare.2

Russia started the war with an enormous stockpile of equipment and ammunition inherited from the USSR, but if the war continues long enough to exhaust that stockpile and for Ukraine’s supporters to shift their economies towards military production it is hard to see how Russia can win.

The Second Amendment

Smith continues his discussion by considering the downside of a professional military and how to deal with it:

Men of republican principles have been jealous of a standing army as dangerous to liberty. It certainly is so wherever the interest of the general and that of the principal officers are not necessarily connected with the support of the constitution of the state. The standing army of Caesar destroyed the Roman republic. The standing army of Cromwell turned the Long Parliament out of doors. But where the sovereign is himself the general, and the principal nobility and gentry of the country the chief officers of the army, where the military force is placed under the command of those who have the greatest interest in the support of the civil authority, because they have themselves the greatest share of that authority, a standing army can never be dangerous to liberty.

The British solution to the threat of a military takeover was a military officered by the people who already ran the government and so had no reason to want to change it. The authors of the U.S. constitution, designed for a younger, less stratified, more fluid society and one without a monarch, chose instead to combine a professional army too small to be a threat with a militia of all able bodied male citizens. Hence the Second Amendment.

A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

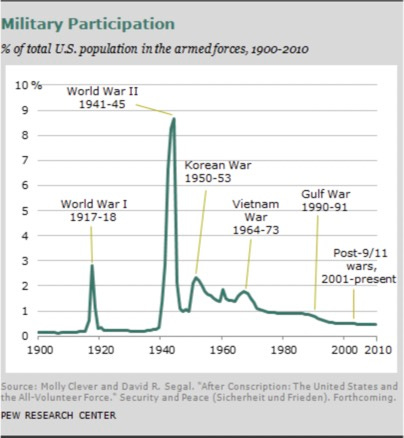

Twice, for the Civil War and the First World War, the military was temporarily expanded by the addition of large numbers of men from the militia, contracted again at the end of the war, but after The Second World War the US shifted to a military system based on a standing army of professional soldiers.

If Smith is correct that should make for a better military — but a more dangerous one.

Including human capital, military training.

If the US stops supporting Ukraine, possible although I think not likely, the remaining NATO countries still have about eight times Russia’s GNP.

We are about to enter a new phase whereas manpower and capital (above a certain minimum) will no longer be the deciding factors, but rather, who has access to a reasonably good AI tech and a concealed factory for producing bio-weapons, and willingness to use them, of course.

I'm actually surprised this hasn't happened yet...

The blueprint is Dune author Frank Herberts lessor known work, The White Plague (1982).

Of course, it's fiction, but the technology required is, if not already developed, about to be. Perhaps not in the same way as the book (whereas men are carries of a plague that only kills women and threatens to end humanity) but nevertheless, the idea isn't that far-fetched, one could dig up bodies n the permafrost and culture the Spanish Flu and release it...obviously anthrax can't be that hard to make as we saw in post-911 attack, etc.

The Demon in the Freezer author Richard Preston talked about (this is decades ago) how his friends, as a hobby, were creating new viruses all the time. What a man in a lab could do previously in a year an AI can already do now in minutes. It will not be long before someone creates something as least as bad as small pox or anthrax or the Spanish Flu, this is axiomatic as they could just stick to making what nature has already provided.

What AI and drone technology allow is a small force to multiply itself by a factor of 10 or 100 thousand, perhaps more. How many men can US brigade kill in day (sans nuclear)? Even if it's 10s of thousands, a small group of people with the right bio-weapon and a few thousand (or even a few hundred) drones could wipe out most of New York or Los Angeles in a few hours work (granted it might take a few weeks before everyone is dead, but the result is the same).

I'm curious, David, why do you think Ukraine hasn't unleashed a bio-weapon in Moscow?

They don't have access to one?

The world would turn against them if they did?

Morality and ethics?

In The White Plague the protagonist unleashes the weapon in England, Ireland, and Libya and demands the world governments instruct those countries to send all citizens of those nations back home and then let the plague run its course. Of course, it's fiction, so things go sideways, but the idea in principle seems sound.

I mean, logical. If you want Russia to end the war, seems like killling off a million citizens out to do the trick as long as you can back up your next threat, i.e. if you don't pull out your troops, next attack will kill 10 million....

I never understood the idea of "War Crimes" in that, if your defending your home, seems like all bets are off.

It's like the little birdie analogy you've used in your libertarian talks, i.e. the little birdie is willing to fight to the death to defend it's territory with a no-holds-barred strategy. "We're both gonna die if you attack, so think twice, bigger bird."

Ultimately I think this is the only way a libertarian or anarchist or any type of new country based not on geography but ideals is going to be able to form and survive, it must have a weapon so dangerous and so unstoppable, the big countries must respect it.

Heinlien taught me this in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. The gravity well of earth meant that the moon citizens could simply hurl boulders and they'd turn into WMD.

I'm not sure there's such a divide between the British and American model. By continental European standards the British army has always been risibly small, and required vast expansion for the world wars; and local militias used to be a significant part of the armed forces (and in a sense, with the Territorial Army, still are).

Undeniable that efficiency was always secondary to a desire for the British army to have interests identical to those of the ruling class, though. I recently found out that even as late as the early twentieth century an officer's salary wasn't sufficient to allow you to marry and have children, unless you had another source of income.