Beyond Rationality?

Rationality is the central assumption of economics. That makes work that challenges that assumption interesting to economists for at least two reasons. One is that we might be wrong; rationality might not be the best way of predicting and explaining human behavior. The other is that such work might expand our understanding of how it is rational to behave. My favorite example of both is Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman, a psychologist who won, and probably deserved, a Nobel prize in economics. Its subject is how the human mind works, why we make the particular mistakes that we make. It thus presents a challenge to my old argument in favor of the rationality assumption:

…the tendency to be rational is the consistent, and hence predictable, element in human behavior. The only alternative to assuming rationality, other than giving up and concluding that human behavior cannot be understood and predicted, would be a theory of irrational behavior, one that told us not only that someone would not always do the rational thing but also which particular irrational thing he would do. So far as I know, no satisfactory theory of that sort exists. (Price Theory, Chapter 1)

Perhaps one now does.

Kahneman’s central insight is that we act as if we had two different mechanisms for making sense of the world around us and deciding what to do. System 1 works automatically and very quickly to recognize a voice over the phone, tell whether a stranger's face is expressing anger, generate conclusions on a wide range of subjects. System 2, conscious thought, takes the conclusions generated by System 1 and either accepts or rejects them in favor of its own conclusions, generated much more slowly and with greater effort. Attention is a limited resource, so using System 2 to do all the work is not an option.

System 1 achieves its speed by applying simple decision rules, some of which can be deduced from the errors it makes. It classifies gambles into three categories: impossible, possible, or certain. An increase in probability within the middle category, say from 50% to 60%, appears much less significant than an increase of the same size from 0% to 10% or from 90% to 100%.1 That offers a possible solution to an old problem in economics, the lottery-insurance puzzle. If someone is risk averse he buys insurance, reducing, at some cost, the uncertainty of his future. If someone is risk preferring, he buys lottery tickets, increasing, at some cost, the uncertainty of his future. Why do some people do both?

Insuring against your house burning down converts a very unattractive outcome (your house burns down and you are much worse off as a result) from probability 1% to probability 0%, a small gain in probability but a large gain in category (from possible to impossible). Buying a lottery ticket converts a very attractive outcome (you get a million dollars) from probability 0% to probability .000007%, a small gain in probability but a large gain in category (from impossible to possible). Both changes are more attractive to System 1 than they would be to a rational gambler so both may seem, to the same person, worth doing.

One of the attractions of Kahneman's book is that, although some of his evidence consists of descriptions of the results of experiments, quite a lot consists of converting the reader into an experimental subject, putting a question to him and then pointing out that the answer produced by the reader’s system 1, the one most people offer, is provably, indeed obviously, wrong.

Consider the following example:

Linda is thirty-one years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is she more likely to be:

A bank teller

A bank teller and active in the feminist movement

Most of the people to whom the question was put judged the second alternative as more likely than the first, despite that being logically impossible. System 1, having a weak grasp of probability, substitutes for the question it cannot answer an easier question it can: “Which sounds more like a description of Linda?”

One interpretation of Kahneman’s work is that we now have a theory of irrationality. By studying the rules of thumb that the fast mind uses we can predict not merely that people will not always make the rational choice, which we already knew, but, sometimes, what irrational choice they will make.

Another interpretation is that Kahneman has expanded by a little our understanding of rationality. We already knew that its simplest version — people always choose the right action — had to be qualified to allow for information costs. Spending a hundred dollars acquiring the information needed to discover which of two brands of car to buy is irrational if the difference between the two is less than two hundred dollars, since a random choice would get the right answer half the time. What Kahneman demonstrates is that we need to take account not only of the cost of getting information but the cost of processing it. The rational choice is to use the low-cost mechanism, the fast mind, for most decisions, the high cost, available in more limited quantity, for the most important ones.

A third interpretation of some of it, such as his discussion of choice under uncertainty, is that we have expanded our understanding of rationality by including the emotions associated with outcomes as well as the outcomes themselves. When you buy a lottery ticket you not only get a very small chance of winning a lot of money, you also get a certainty of being able to daydream about what your life would be like if you won, daydreams that are more vivid and pleasurable if they have some chance, however small, of happening. When you have a 95% chance of losing a law suit for $10,000 and turn down an opportunity to settle for $9000 you are missing an opportunity to reduce your expected loss but you are also retaining the possibility of avoiding the unpleasant emotions associated with losing, getting the pleasant emotions from winning. A more detailed theory of rational choice would include that kind of cost and benefit along with the direct costs and benefits of winning or losing a gamble.

Kahneman makes this point in his discussion, writing, for example:

Of course, what people acquire with a ticket is more than a chance of winning; it is the right to dream pleasantly of winning.

I made the same point more than twenty years before Kahneman’s book was published,2 writing in the discussion of the lottery/insurance puzzle:3

Consider the lotteries you have yourself been offered — by Reader's Digest, Publisher’s Clearinghouse, and similar enterprises. The price is the price of a stamp, the payoff — lavishly illustrated with glossy photographs — a (very small) chance of a new Cadillac, a Caribbean vacation, an income of $20,000 a year for life. My rough calculations — based on a guess of how many people respond to the lottery — suggest that the value of the prize multiplied by the chance of getting it comes to less than the cost of the stamp. The expected return is negative.

Why then do so many people enter? The explanation I find most plausible is that what they are getting for their stamp is not merely one chance in a million of a $40,000 car. They are also getting a certainty of being able to daydream about getting the car — or the vacation or the income — from the time they send in the envelope until the winners are announced. The daydream is made more satisfying by the knowledge that there is a chance, even if a slim one, that they will actually win the prize. The lottery is not only selling a gamble. It is also selling a dream — and at a very low price.

One example Kahneman offers of irrational behavior is the willingness of a country to keep fighting even after the war is almost certainly lost.4 An alternative explanation is that, by committing itself to act that way, perhaps by promoting the belief in its population that surrender is more shameful than defeat, the country makes conquering it more expensive hence less likely to be attempted. Ex post the action is irrational but ex ante committing to it may be rational. A similar explanation might apply to the individual who rejects a $9000 settlement offer. He would be better off settling but the knowledge that he is the sort of person who refuses to settle makes suing him less attractive since it raises the legal cost of suing him. The behavior may be irrational but the commitment strategy that produces it need not be.

Economists have always known that their models simplify choice in the real world, since even if individuals are perfectly rational the costs and benefits they face are more complicated than the costs and benefits included in our equations. The question is whether factors not included in the models can be added without losing more in additional complication — a sufficiently elaborate model can fit anything and predict nothing — than they gain in greater realism. The test is whether the expanded model does a better or worse job of predicting things we do not already know.

Kahneman has provided some intriguing candidates for expanding our models. It is less clear whether he has also provided evidence that our central assumption is false, less clear still evidence that it is not useful.

Kahneman and Caloric Leakage

The malfunctions of the fast mind may help explain why it is so hard to lose weight. Consider caloric leakage, the principle that holds that although a cookie has lots of calories a piece of a broken cookie does not, the calories having leaked out, so you might as well eat it. Or consider my well-established weakness for marginal cost zero food, another serving at an all-you-can-eat buffet.

The explanation for the belief in caloric leakage is the inability of my fast mind to deal with fine distinctions. A piece of a cookie is different from a cookie so my knowledge that it has half the calories of the cookie never gets triggered. The explanation for my weakness to temptation is that, faced with zero marginal cost food, I have no need to pass the decision of whether to eat it to my slow mind in order to decide whether it is worth the cost in money and my fast mind does not worry about the cost in calories.

Also, my fast mind has a high discount rate, is reluctant to give up benefits now for larger benefits in the future. And I like cookies.

When I offered this somewhat tongue in cheek application of Kahneman’s ideas on my blog, one commenter replied:

My slow mind has long since stopped letting my fast mind into all-you-can-eat buffets.

Are these Facts True: The Replication Crisis

So far I have taken it for granted that the facts on which Kahneman based his theories were true. Reporting on some of them, he wrote:

When I describe priming studies to audiences, the reaction is often disbelief . . . The idea you should focus on, however, is that disbelief is not an option. The results are not made up, nor are they statistical flukes. You have no choice but to accept that the major conclusions of these studies are true.

We now know that he was wrong. When other researchers attempted to replicate those studies they were for the most part unable to do so. That was part of what came to be known as the replication crisis, largely but not entirely in psychology. Most of the most prominent and striking results in the priming literature turned out to be bogus. There was one notable case of deliberate fraud by a prominent researcher but it seems likely that most of what happened was honest error. Researchers did not adequately understand how easy it is to get apparent confirmation for a false theory that you want to be true.

One way of doing so is illustrated by the Texas sharpshooter story:

A visitor to a Texas town observes a man with a rifle who has been shooting at a barn some distance away. The barn wall is peppered with bullet holes, each in the precise center of a painted circle, clearly an impressive performance. While he watches, the sharpshooter takes another shot, walks up to the barn with a pail of paint and a brush and paints a circle around the bullet hole.

You want to know whether a particular supplement slows aging. You test two hundred people for biological markers of aging, put a hundred on the supplement and a hundred on a placebo for two years, then test them again. The average amount of aging in the two groups is about the same, which is disappointing

But that is only the first step in analyzing the data. Perhaps the supplement works for men but not for women or for women but not for men; you analyze the data separately for each group. Perhaps it slows aging in the elderly but not the young, or the young but not the elderly. Perhaps it works only for elderly women. Perhaps it slows aging for the first year of the experiment but not the second, or the second but not the first. Perhaps …

You end up with twenty different versions of “the supplement works,” test them all, and find that one of them gives a statistically significant result. You conclude that the supplement slows aging for elderly men, has little effect on other groups.

Statistical significance is a measure of how likely it is to get your result by pure chance. A significance of .05, often used as a cutoff, means that you have about one chance in twenty of getting a result that good by accident. You have done twenty different experiments so it is not surprising that you got lucky once.

This is the Texas sharpshooter fallacy, choosing the theory you are testing only after looking at the data you are using to test it. One way to avoid it and prove to others that you have done so is to preregister your research project, state what theory you are testing before, not after, you collect and analyze the data. You no longer have the option of selecting whatever theory best fits your data and reporting only on it.

The same problem can occur through a different mechanism: publication bias. Twenty different researchers do similar studies using twenty different supplements, each carefully preregistering. Nineteen of them get no result. Since failing to discover something is not very interesting, none of them publish. One gets lucky. His result, significant at the .05 level, is the only one that the rest of the field sees.

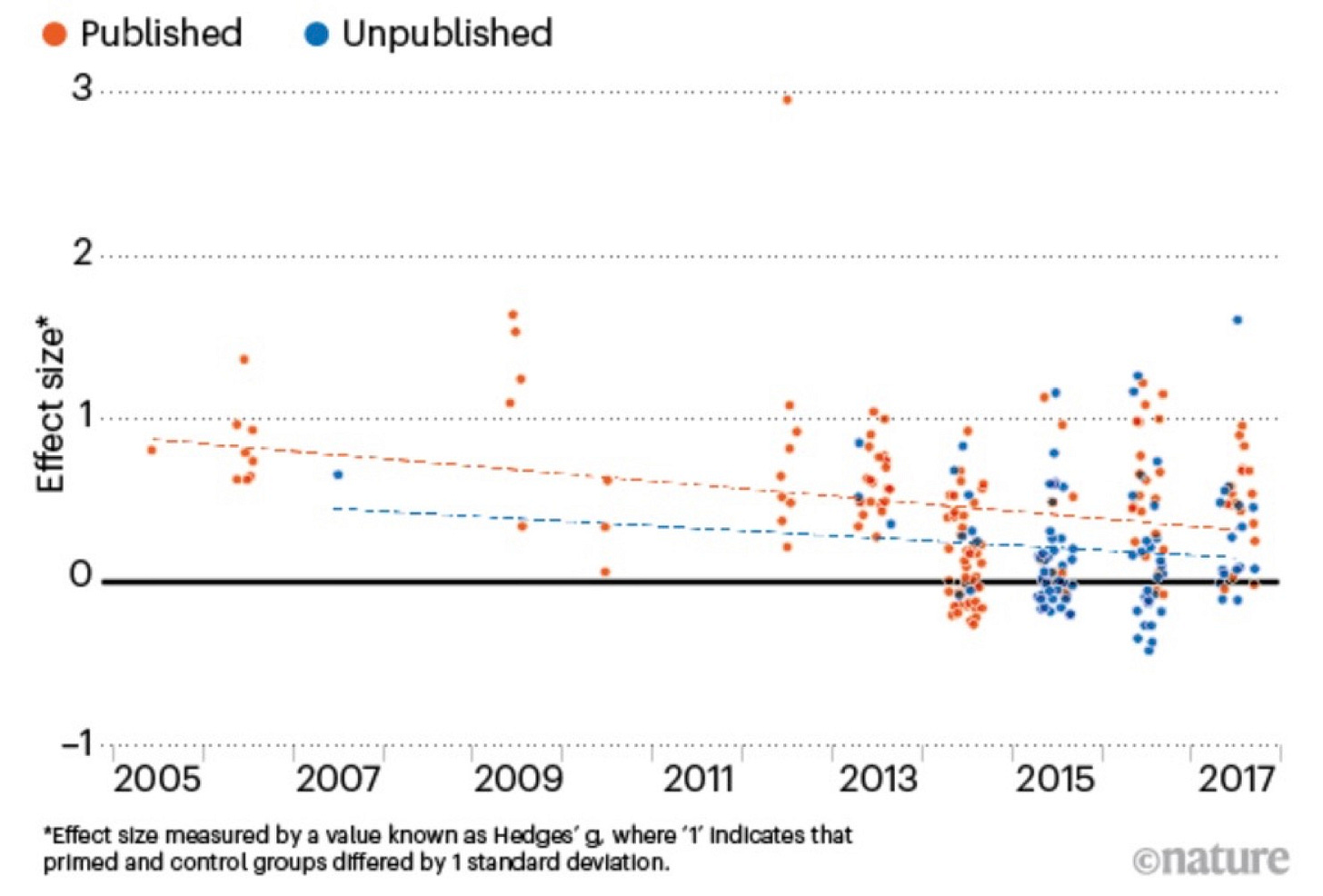

One of the studies done during the replication crisis looked at experimental results that were not published as well as ones on the same subject that were. The published experiments showed results that fit the theory, the unpublished did not.

Source: P. Lodder, based on data from Lodder, P., Ong, H. H., Grasman, R. P. P. P. & Wicherts, J. M. “A comprehensive meta-analysis of money priming, J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 148, 688–712 (2019).

Another source of false results is the tendency for people to see what they expect to see; even a small number of errors, all in the same direction, can raise random data to significance. One attempt at multiple replications of a prominent priming result discovered that it only worked if the people observing and recording the results were told what result they were looking for.5

The more general problem is the system of incentives. Academics get jobs and promotions by publishing articles, so have a strong incentive to produce publishable results. A true theory is more likely to have already been discovered and published than a false one, making the latter more likely to be novel and, if it appears to be supported by evidence, publishable. Peer review can spot some sorts of errors but not all; the reviewer has to take the data as he gets it and has no way of knowing if what is being reported is the first or the twentieth, version of the experiment. In the case of priming research these incentives produced a body of results widely accepted in the field which now appear to be mostly false, results that played a substantial role in Kahneman’s work.

As he wrote in 2017:

Clearly, the experimental evidence for the ideas I presented in that chapter was significantly weaker than I believed when I wrote it. This was simply an error: I knew all I needed to know to moderate my enthusiasm for the surprising and elegant findings that I cited, but I did not think it through. When questions were later raised about the robustness of priming results I hoped that the authors of this research would rally to bolster their case by stronger evidence, but this did not happen.

I still find Kahneman’s overall argument convincing, more for the experiments in which I was the subject than those he reported. He is probably correct that the mistakes we make can be to some extent predicted but his conclusions about what the pattern is and why were too confident.

I am simplifying. Kahneman’s much more detailed account of the fast mind’s view of decision under uncertainty is in Chapter 29 of Thinking, Fast and Slow.

But perhaps not before he first made the point elsewhere. Kahneman and Tversky wrote about the pattern of choice under uncertainty at least as early as 1979 (“Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk”) but a quick look through the article did not find any discussion of the relevance of emotions associated with choices.

Price Theory:An Intermediate Text, third edition, Chapter 13, pp. 320-321.

This is a poor example for Kahneman’s purposes for another reason: Rationality is an assumption about individuals not groups. Irrational behavior by governments is consistent with, indeed arguably predicted by, rational behavior by individuals, a point I discuss in Chapter 53 of The Machinery of Freedom.

Doyen, S., Klein, O., Pichon, C-L. & Cleeremans, A., “Behavioral Priming: It's All in the Mind, but Whose Mind?” PLoS ONE 7, e29081 (2012).

This is a fantastic post about the replication failures / TX sharpshooter. IMO, it would be great to have that as a stand-alone w/o the Danny stuff.

>a psychologist who won, and probably deserved, a Nobel prize

To my eye, this ("probably") sounds like petty jealousy. Like you're smarter than the Nobel committee.

>I made the same point more than twenty years before Kahneman’s book was published

Yeah, but Danny and Amos were doing this work many years before your bit. ;-)

Danny only got to writing his magnum opus later.

>results that played a substantial role in Kahneman’s work.

This is most definitely wrong -- priming was just one small part of his work.

Since I was first exposed to their work in the 90s, I have found evolutionary psychology to be the main source of insight. We're "rational" in that our minds work to get our genes to the next generation ... in our evolutionary setting.

IMHO.

Dan Ariely's book _Predictably Irrational_ makes the same point as the first half of your post: that not only is a lot of human economic behavior "irrational" in the economist's sense, but it's _consistently_ and _predictably_ irrational, not just noise. For example, under certain predictable circumstances, people treat "free" as dramatically less expensive than even the smallest positive price, and under other predictable circumstances, people treat "free" as equivalent to quite a high price. ("Why are you doing this for free? I'm willing to pay you." "Because if you paid me what I'm worth, you couldn't afford me.")

It too quotes a lot of experiments, and it would be interesting to see how those experiments have fared under replication.