Dumb Facts

It is sometimes said that facts speak for themselves, but mostly they don't. For one example, consider media reports on the relation between the 2008 bailout and the stock market. When the House voted down the bailout and the market fell, the fall was reported as a response to the failure. When the House passed the bailout and the market fell, the fall was reported as occurring in spite of the passage of the bailout.

In this case as in many others, once you have your conclusion you can almost always arrange for all evidence to be consistent with it.

Global warming provides another example. If the weather somewhere feels warmer than usual, that is evidence of global warming; the fact that total global warming in the past century comes to about one degree centigrade, too slow for anyone to notice in his own lifetime, is not usually mentioned. If the weather is colder than usual that is evidence of changing weather patterns due to global warming.

It used to be said that the poor agricultural performance of the Soviet Union was due to worse than average weather—forty straight years of it. No doubt it was true. In a country that big, the weather is always worse than average somewhere.

Age Related Fertility Decline and the Link Between Facts and Policies

Some years ago I heard a talk by a colleague on the issue of age related fertility decline in women. Her basic claim was that although women know it exists, most badly underestimate how serious the problem is and how limited a solution assisted reproductive technology provides, with the result that many women who want children end up not having them. One policy proposal she offered was that sex education classes ought to include information on fertility decline. It struck me, listening to the talk, that in this case as in many others the same facts can be used to support a wide range of different political conclusions.

In this case ...

It sounded as though opposition to the idea of warning women about the risks, including criticism of the data on which the warnings were based, came largely from feminists concerned that such warnings would scare women out of career paths that included delayed motherhood. That is indeed one possible consequence. Pushing the argument further in that direction, one could argue that fertility decline is not only an argument in favor of the traditional family pattern, women marrying young and putting most of their efforts into the job of wife and mother, it is also an argument in favor of traditional sexual mores. In order for women to marry young there have to be men willing to marry them; one reason why, in a more traditional society, men were willing to marry was that it was the only reliable way of getting sex. The more common and accepted nomarital sex is, the weaker that incentive.

On the other hand ...

Someone with a different political orientation could use the same facts to argue for a different set of conclusions. If you take the importance of career options for women as a given, fertility decline becomes a reason why husbands should do more of the work of taking care of children, employers be more willing to provide on site nurseries, offer extended periods of leave or part time work to new mothers, why social institutions should change to make it easier for women to combine career and motherhood before they get too old to make the latter a reliable option.

Similar considerations apply to the proposal to include information on fertility decline in sex education. As another member of the audience pointed out, that might make sex education more popular with conservatives since it would be teaching how to have babies as well as how not to have them, the latter being how current sex education is often viewed.

On the other hand, one might argue that fully accurate information about fertility would have a perverse effect, at least one that conservatives would disapprove of. Current campaigns pushing contraception to teens leave the impression that unprotected sex is likely to lead to pregnancy, which is an argument for contraception but also against sex, abstinence being the simplest and most reliable way of avoiding pregnancy. Accurate information, as best I can tell by a little online search, would tell students that a single act of unprotected intercourse, randomly timed, has only about one chance in forty of resulting in pregnancy—less if the couple make an attempt to avoid the woman's fertile period. To amorous teenagers one chance in forty might look pretty safe, especially if they tell themselves that they are only going to try it once. So accurate information, not about fertility decline but about fertility, might easily produce an increase in the teen pregnancy rate.

My own conclusion from such considerations is that the best rule is to try to tell the truth. Whatever information you provide people you cannot predict how they will use it, so trying to bias the facts to produce the result you want is likely not to work, might have the opposite of the intended result. If you tell people the truth, you at least reduce one source of incorrect decisions. That is part of why, in my talks and writing, I try to give the arguments against my positions as well as the arguments for.

In support of which immodest claim I offer Chapter 55 from part V of the third edition of my first book, which presents and discusses an argument against the stability of the set of institutions that I spent part III of the book describing and defending.

While on the subject of sex education, one example of people teaching not what they believe is true but what they want students to believe was reported to me by my elder son, who went to a suburban Philadelphia public school. As he described it, the course treated AIDS as just another STD, with no explanation of differences in how it was transmitted.

My conjecture is that this was a response to political pressures from opposite sides. People on the right wanted to scare kids away from sex, which an incurable STD helped to do. People on the left wanted to keep AIDS from being identified as a gay disease, which hiding the fact that it was much more readily transmitted by anal than by vaginal sex helped do.

That is what is described, in a different context, as a Baptists and bootleggers coalition.

Status Stability Over Time

Italian researchers looked at data on income, wealth, and profession in Florence in 1427 and similar data for 2011 to investigate how stable socioeconomic status had been over long periods of time, to what extent having rich ancestors six hundred years ago makes you rich today.1 While they did not have detailed ancestry data they did have last names, so could see how close the relation was between someone with a particular surname at present and people with the same name, some presumably his distant ancestors, then.

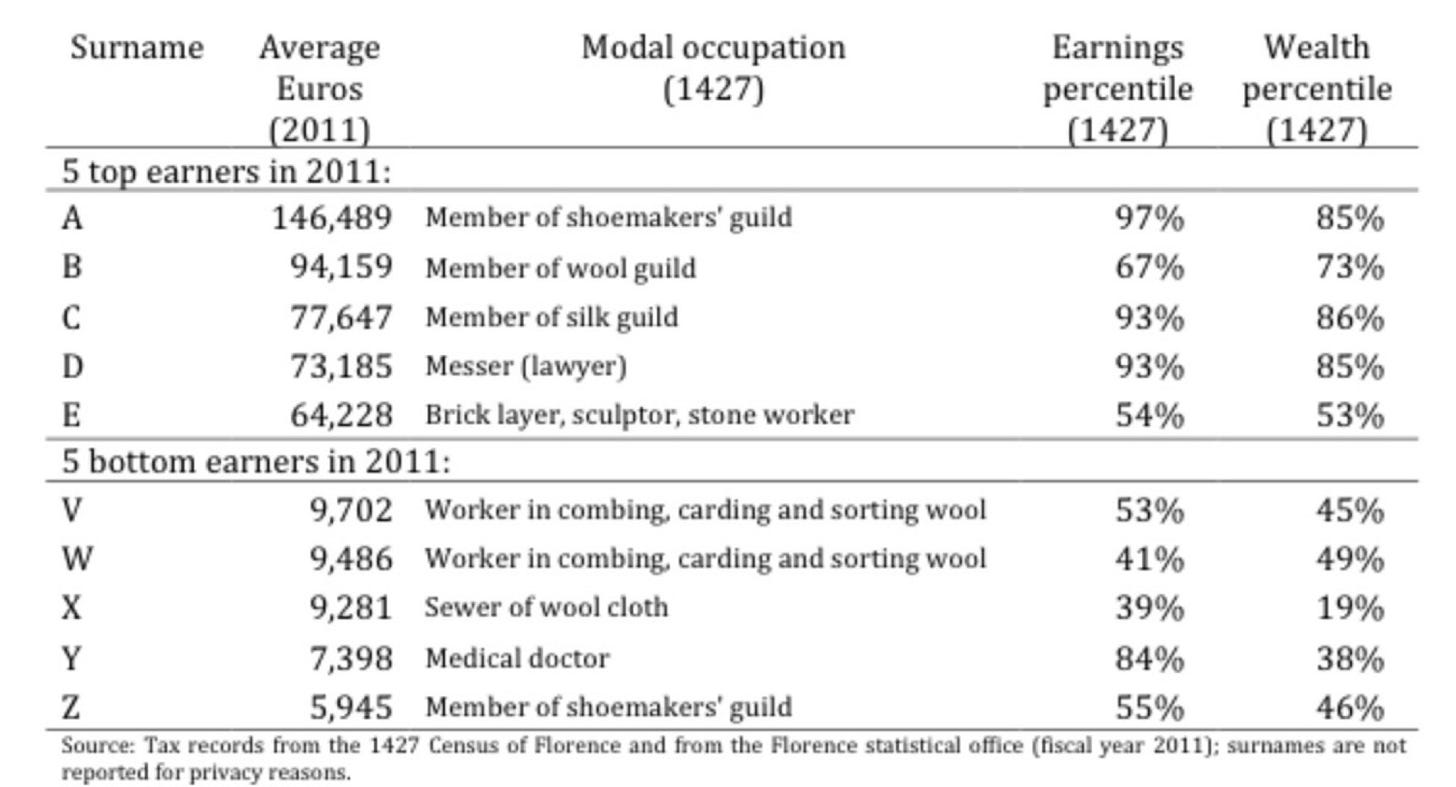

Table 1 offers a first flavour of our results. We report for the top five and bottom five earners among current taxpayers (at the surname level) the modal value of the occupation and the percentiles in the earnings and wealth distribution in the 15th century

Their conclusion was that, even after six centuries, family dynasties were stable enough to give a small but statistically significant correlation of income, wealth, and professional status between ancestors and descendants.

Stated differently, being the descendants of the Bernardi family (at the 90th percentile of earnings distribution in 1427) instead of the Grasso family (10th percentile of the same distribution) would entail a 5% increase in earnings among current taxpayers (after adjusting for age and gender).

There are two possible interpretations of the reported facts. One, pretty clearly that of the authors,2 is that families are surprisingly good at passing wealth and status down from one generation to another. The other is that the characteristics that produce wealth and status are to a large extent heritable. The data offered in the article provide no way of distinguishing between the two.

One problem for the second interpretation is that last names and, to a considerable degree, wealth were passed down in the male line, talents passed down through both sons and daughters. That is a less serious problem than it at first appears because high status women mostly married high status men. The daughter of a wealthy Florentine family would usually combine her genetic heritage with the last name of a husband from a different wealthy Florentine family. Hence both genetic advantages and wealth would for the most part remain, from generation to generation, associated with the same pool of last names.

How you interpret facts depends on the picture of the world you fit them into, in this case which side of the nature/nurture controversy you find more plausible.

A commenter on this post pointed me at an article about some work along similar lines using English data which takes the genetic explanation seriously, notes that in order for genetic differences to be stable over time there has to be a good deal of assortative mating and that, due to the English class system, there was. That suggests the very politically incorrect conclusion that there was, perhaps is, a correlation between class and ability.

P.S. For my first 98 posts I have been sending them out every two days. I have decided to switch, at least for a while, to a post every three days, to leave me more time for other writing projects. That is why this one did not come out yesterday.

Sauro Mocetti and Guglielmo Barone, “What’s your (sur)name? Intergenerational mobility over six centuries,” VoxEU, 17 May 2016.

They write “Societies characterised by a high transmission of socioeconomic status across generations are not only more likely to be perceived as ‘unfair’, they may also be less efficient as they waste the skills of those coming from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

That assumes that the higher status is not due to greater skills.

A similar discussion of last names and wealth over time can be seen here (Britian) https://www.takimag.com/article/class-and-family/

>the fact that total global warming in the past century comes to about one degree centigrade, too slow for anyone to notice in his own lifetime

Does the former necessarily imply the latter? While a 1 C shift in mean temperature is not noticeable, shifting the temperature distribution to the right by even a fraction of a degree, might be noticeable on the tails, as the density of the leftmost tail decreases a lot, and the density of the rightmost tail increases a lot.

For example, if a city has a mean temperature of 12 C and a SD of 10 C, only 0.1% of days would be 42 C or above, but if the mean rose to 12.5 C, the share of days 42 or above would double to 0.2%.

[I'm assuming each day has a single temperature for illustrative purposes.]