Home Economics

Economics is a tool for understanding human behavior.1 That includes problems in running a household. For example …

Solutions to a Public Good Problem

Emptying and refilling ice cube trays requires about ten minutes that could be spent doing something more entertaining such as reading a good book or arguing with people online. If I do it the benefit is shared with my son and daughter, if one of them does it the benefit is shared with me (my wife doesn’t have a taste for iced drinks). There is a temptation for each of us to refrain from emptying the trays into the bin until we absolutely have to in the hope that one of the others will do it instead.

That is a public good problem.

One solution would be to convert the public good to three private goods, three sets of ice cube trays and three bins, one for each for each of us, but space in the freezer compartment of the refrigerator is a scarce resource and we don’t have room for three refrigerators. Another solution would be to charge each of us for each ice cube used, paying the money to whomever emptied the trays, with the price adjusted until quantity supplied equaled quantity demanded. But … transaction costs.

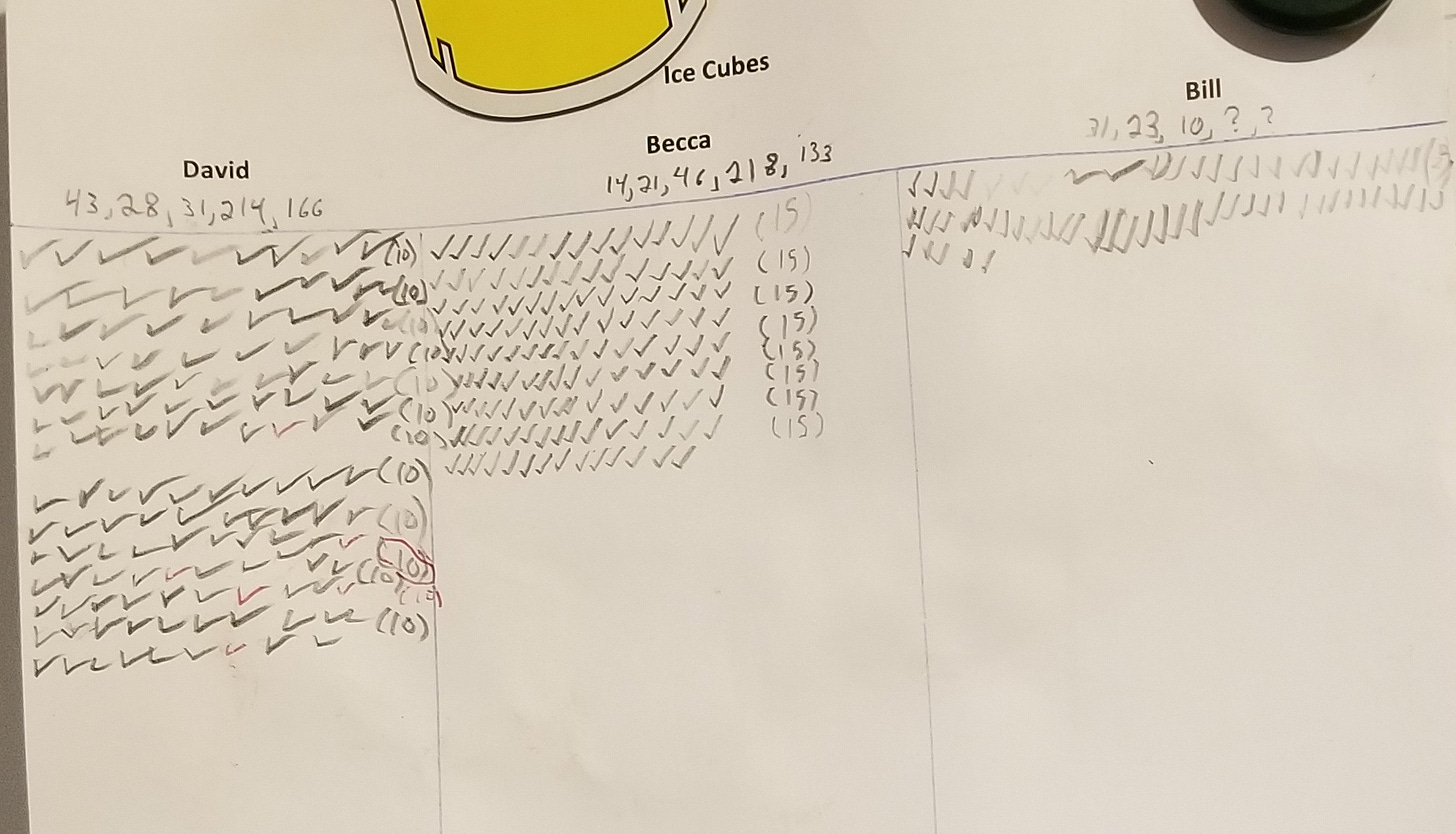

The solution I found was to convert the public good problem into a competitive game. A sheet of paper on the refrigerator keeps track of how many times each of us has emptied the ice cube trays and we compete to stay ahead. That is why, if you happened to be in the kitchen at the right time, you might hear my son saying “Dibs on the ice cubes” or my daughter, having noticed that I have the bin out to refill it, complaining that she was about to do so.

It is tempting, in order to get a point before someone else beats you to it, to refill the bin at the earliest possible moment when there is just barely enough room for the additional cubes. If you get it wrong …

Solutions bring their own problems.

Who Washes the Dishes?

Consider a household of two people, both cooks. Assume away any differences between their circumstances that might be relevant to who washes the dishes when. Assume each of them cooks about half the time. When one of them cooks, which of them should wash the dishes?

A moral philosopher might say that the non-cook should wash the dishes since it is fairer to distribute the burden. But my cooking and washing one day, my wife the next, is just as even a distribution as my cooking one day and her washing, her cooking the next and my washing. And besides, I am an economist not a moral philosopher.2

When I put this to an audience as a puzzle the one who gets the right answer is usually someone who cooks, so knows that how much cleaning up needs doing depends on choices made by the cook. Does he cook a meal that requires a frying pan, a sauce pan, and a baking dish, all of which will have to be washed, or a one pot meal? When the pot with the second stage of the recipe is coming to a boil does he sit and watch it or take the opportunity to put the first stage pot in the sink and fill it with water to soak? How careful is he to keep stirring the contents of the pot so as to be sure nothing sticks to the bottom, burns, and will require half an hour of scrubbing to get off?

A cook who washes his own dishes has an incentive to minimize the combined work of cooking and cleaning. If one person cooks and the other washes up, the cook has less incentive to make decisions that minimize the amount of cleaning up and less information for doing it. The conclusion that the cook should wash his own dishes holds even if the two cooks are a loving husband and wife each of whom values the happiness of the other, because washing up after a meal generates useful information about much work that particular meal prepared in that way generates.

The rule in our household, which has three cooks, is that the cook cleans up after himself or herself. Even though we all love each other.

Eat Your Spinach

A common child-rearing problem is getting the child to eat what the parents want him to. Common solutions include “no desert if you don’t eat your spinach,” “No seconds on spaghetti until you finish your vegetables,” and stronger variants up to and including “you will sit there until you eat your squash.”

My wife, as a child, experienced the last. Her mother liked acorn squash. Betty detested it, eventually refused to eat it. Told that if she didn’t eat it she couldn’t have desert she still didn’t eat it. Told that she couldn’t leave the table until she ate it, she sat. At her bedtime she was still sitting; the final compromise was one small spoonful of acorn squash. That was the last time her parents tried to feed it to her.

On the theory that children resemble their parents we decided not to try that approach.

The problem, from the standpoint of both economics and libertarian child-rearing, is how to align incentives, to make it in the interest of the child to do what we thought was good for him. The starting point was to recognize that the objective was not to make the child obey us but to get him adequate nutrition without giving him a veto on what the rest of us had for dinner or our having to do the additional work of making a different meal for him.

The solution was that he did not have to eat what he was offered provided he could come up with something we considered nutritionally adequate that required no additional work on our part. It was up to him to find something that qualified.

Most often blueberry yogurt.

Reducing the Cost of Acknowledging Error

My parents invented a family code, numbers that stood for sentences. One item in that code has survived in my family. “Number two” means “You were right and I was wrong.”

Admitting error is hard. Using a code for it reminds the speaker that it is a hard thing to do, hence that he should be proud of doing it. Using a family code reminds him that he is conceding error not to a cold hard world whose residents will mock him for error but to people he can trust not to.

P.S. After posting this, I came across the following on X:

I had a coworker a decade ago who had two dishwashers in his kitchen. He’d fill one dishwasher with dirty dishes, run it, and then that was the clean dishwasher. Then dirty dishes went in the other one. He never had to put dishes away.

As I sometimes put it in explaining why, there is a reason that philosophers still read Aristotle and economists don’t.

Enjoyed this post on several levels. I'm of a similar age bracket to you and my parents, having grown up in the Depression were averse to anything resembling wastefulness, particularly when it came to food. So any resistance my brothers and I put up over certain foods was not well tolerated. In my case, I ate almost anything but my next brother despised peas and broccoli, spending long periods of time staring at the offending vegetables until he "cleaned his plate." But he ate nearly everything else without complaining and, to my parents' credit, eventually gave him a pass on those two foods. Harmony at the dinner table was returned to normal and nobody starved to death.

When I was a child we had a rule that has persisted now to my great-grandchildren. Children have new, or different, or unusual foods on their plates (in about a tablespoonful in total), and they must eat two bites (Mom decides the size of the bites), but after that they are free to ignore it until the next time it appears on the plate. After three tries they no longer have to eat that food until they "grow up" and they may choose to try it again. We just served them all plenty of home made cooking and very little sugary snacks. So far it works well.

My children both love spinach, raw or cooked despite their mother (a vegetarian) not liking it at all. Each of them eats a wide variety of foods (my daughter is now a "mostly vegetarian" who, oddly eats very spicy chili with hamburger in it occasionally). My son eats pretty much anything put in front of him. Their grown children are also pretty much "eat anything" types.

I think the trick is allowing some decision-making by children when they're quite young.

As an aside, as a baby my son would not eat any green baby food. Not green beans, not peas, not spinach. I would try to trick him by giving him a spoonful of half apricots, which he loved, and half green stuff. At 8 months he'd wallow the food around with his tongue, then spit out the green stuff every time. I still have no idea of why, or of how, exactly, he knew. Today he likes all of those green veggies.