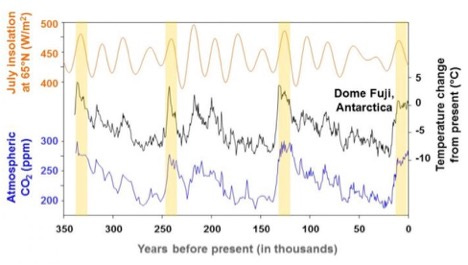

The figure shows temperature, CO2 concentration and insolation for the past 350,000 years, a period that covers four interglacials, shown as yellow columns. The last is ours. In the first three, temperature follows the same pattern, rising steeply at the beginning then falling until the end. CO2 concentration follows a similar pattern except in the third interglacial, where it oscillates about a constant or slightly rising level.

The pattern in the fourth interglacial is quite different. For the first few thousand years it is similar to the previous three, then the pattern reverses, with temperature and CO2 rising instead of falling through the rest of the interglacial.

What was different this time? The obvious guess is us. The reversal in the pattern happens at about the time that humans adopted agriculture, resulting in a large increase in human population and a change in how humans affected the world around them.

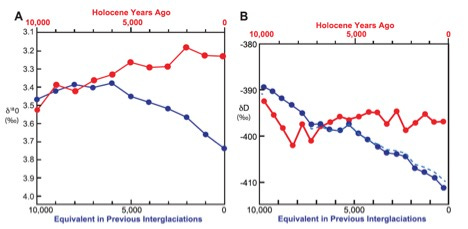

That possibility occurred to me when I first saw the graph but I did not know enough to tell if it was plausible, if anything humans did prior to recent centuries was large enough to affect global temperature and CO2 levels. Someone in an online discussion pointed me at the work of William Ruddiman, who noticed the pattern some twenty years before I did and published on it, proposing what became known as the Early Anthropogenic Hypothesis. His conjecture was that deforestation, starting about eight thousand years ago, had put enough CO2 into the atmosphere to raise global temperatures. Data on the concentration of methane, another greenhouse gas, showed a similar divergence from the pattern of previous interglacials starting about five thousand years ago. He attributed that to the development and spread of irrigated rice farming, methane being produced by drowned vegetation. The comparison between what happened in the current interglacial and in previous interglacials is shown for CO2 in Figure A, for CH4 in figure B.

Fig. 9. Comparison of Holocene trends (red) to stacked averages for previous interglaciations (blue), from Ruddiman et al. (2016) (A) Benthic d18O stack from Lisiecki and Raymo (2005) and B). Dome C dD stack from Jouzel et al. (2003).1

His conclusion:

This comparison thus suggests that a glaciation should have begun several thousand years ago in northeast Canada. Early anthropogenic emissions of CO2 and CH4 are the most likely reason that it did not. (Ruddiman 2003, p. 2882)

In addition to offering an explanation for the broad pattern, Ruddiman argues that human influence on climate explains climate changes in the historical past, with the reduction in global population due to pandemics such as the black death causing large scale abandonment of farmed or grazed land which then reforested, pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere and causing a temporary drop in its global concentration.

Ruddiman’s paper set off a controversy that is still running. Inputs to the controversy included archaeological evidence on the size of early populations, pollen evidence for the extent of forests, climate modeling, isotope ratio evidence for the sources of atmospheric CO2 and much else. Alternative explanations for the pattern were rejected by supporters of the hypothesis primarily on the grounds that they would have applied to earlier interglacials. Interested readers will find a summary of the state of the argument as of 2020 in the review article by Ruddiman et. al.3 Its updated version of the hypothesis, which has the CO2 rise starting about seven thousand years ago, includes a variety of complications, none of which change the essential features of the conjecture.

The evidence from MIS 19 [an earlier interglacial whose circumstances closely match the current one] suggests that human interference in the operation of the climate system by greenhouse-gas emissions during the Holocene kept ice from accumulating in north-polar regions. The late Holocene was a time in which interglacial warmth persisted only because of early farming. (Ruddiman et. al. 2020)

Getting Back to the Present

One of my criticisms of estimates of the net effect of climate change, in particular the estimates by Nordhaus, is that they try to include estimates of low probability high cost consequences of climate change, things that probably won’t happen but would be very bad if they did, but not of low probability high cost consequences of preventing climate change. The obvious example of the latter is the end of the current interglacial. It has been running longer than most past interglacials and, although we have theories about why interglacials start and end, we do not actually know. We do know the consequences, on the basis of past glaciations — about half a mile of ice over the present locations of Chicago and London and a drop of sea level by several hundred feet, leaving every port in the world high and dry. That would be a very large cost. If Ruddiman is correct, that particular danger has been eliminated by anthropogenic warming in the distant past.

But he might not be.

This is Figure 9 from W.F. Ruddiman, F. He, S.J. Vavrus, J.E. Kutzbach, “The early anthropogenic hypothesis: A review,” Quaternary Science Reviews, Volume 240, 2020, p. 8.

William F. Ruddiman, The Anthropogenic Greenhouse Era Began Thousands Of Years Ago, Climatic Change 61: 261–293, 2003. He estimates the temperature increase as .8°C on average but about 2°C in high northern latitudes where glaciation could start.

For a briefer but more recent summary of the debate, see Rich Blaustein, “The Ruddiman Hypothesis: A Debated Theory Progresses Along Interdisciplinary Lines.”

This is great stuff, as always.

Any chance of putting out two books on climate, a short one for the common man and a long one with the heavy artillery?

Cheers.

People don't understand the risks of glaciation. They think it's completely impossible in spite of the fact that we know it's happened in the past, happened on a schedule, and it's time is now.

I claim that these people have never been cold in their lives. I mean really cold, like -40 cold.