Recognizing Theories

and belief in them

One of the things I did when looking at colleges for my children was to get into conversations with economics professors. Part of the reason was that I have things in common with other economists that I don't have in common with most other people, making it easier to talk with them and get them to talk with me. A second reason was that I wanted to know how tolerant the college's culture was of intellectual diversity.

Economics is neither right wing nor left wing; there have been good economists who were socialists, good economists who were extreme libertarians. It is, in a very real sense, its own ideology. It is almost impossible to be a good economist and accept traditional conservative arguments against free trade, because those arguments depend on not understanding economic ideas worked out nearly two hundred years ago. It is almost impossible to be a good economist and accept common left wing rhetoric about "people not profits" or the equivalent, because a good economist knows that the argument on the other side is not about profits as an end in themselves but about profits as part of a signaling system that results in benefits for people. A left wing economist might think that system works poorly and can be improved by proper government intervention but he knows that the standard left-wing rhetoric misrepresents the position it argues against.

One consequence is that a good economist1 is almost certain to find himself in conflict with the left wing orthodoxy that dominates the sort of top liberal arts colleges we had been looking at, just as he would be almost certain to find himself in conflict with the right wing orthodoxy that (I presume) dominates some Christian fundamentalist schools. So talking to economists at a school gave me some feel for how that school's culture treated heretical views.

The point was initially brought home to me in a conversation with an economist at one of the colleges we visited. She was commenting on the difficulty of teaching environmental economics to students who viewed pollution as a sin, not a cost. Her view of the subject differed from theirs not because she was right wing or left wing but because she was an economist.

It later occurred to me in a different context that there is a more general point buried here. The context was the book The Moral Animal, an exposition of the implications of evolutionary biology, in particular evolutionary psychology. The author argued, I think correctly, that while evolutionary biology is often thought of as a right wing approach, some of its implications provide arguments for left wing positions.

The general point is that one way of recognizing belief in a real scientific theory, in the broad sense in which neo-classical economics, or evolutionary psychology, can be thought of as a single theory, is by its inconsistency with other theories. If a particular point of view is merely a smokescreen for right wing or left wing views it will conveniently produce arguments all of which support the same side. If it is a real theory, an internally consistent body of ideas for making sense of the world, it is almost certain to clash with other ways of making sense of the world. So will the beliefs of someone who believes in it. In principle there would be no clash between theories both of which were entirely true but that is not likely to be an exception of much real world significance.

Both evolutionary psychology and neoclassical economics pass the test. So does the economic analysis of law, the field that was for many years my specialty.

I have put the point in terms of scientific theories, but it applies more broadly as a test of beliefs. If someone claims to be a committed Catholic but all his applications of Catholic doctrine support positions held by non-Catholics with similar political beliefs, or a committed Muslim or fundamentalist Christian with the same pattern, the political belief is probably more fundamental, the religion a useful cloak.

One clue is what arguments matter. If someone claims to support laws against homosexuality because the bible says to, his response to arguments that the destruction of Sodom was punishment not for sodomy but for violation of the norms of hospitality should be look over the arguments and try to answer them not ignore them, and similarly to the claim that the biblical injunction covers male homosexuality but not female.2 If biblical authority is the basis for his view of the subject he should be interested in finding out what the bible says hence what he should believe, instead of starting with what he believes and trying to show that the bible supports it.

The approach applies to judicial philosophy as well. If a judge appointed by a Republican president and confirmed by a Republican senate majority represents himself as a believer in original intent but finds ways of evading original intent when those arguments would require him to restrict the power of a Republican president, we can be pretty sure that his real allegiance is not to the intent of the authors of the Constitution. If, on the other hand, he dissents from conservative doctrine when a reasonable reading of the Constitution requires him to do so we can be pretty sure that his judicial philosophy, whether or not it is correct, is at least his.

Covid provides at least one example of behavior inconsistent with announced theory. There was some reason to believe that a well constructed N95 mask properly worn would reduce contagion. There was very little reason to believe that a simple cloth mask would do it. But masking requirements, when imposed, were routinely interpreted as satisfied by either. Even after good masks became widely available there was very little attempt to instruct people on how properly to adjust them. It felt very much as though wearing a mask was being treated as a symbolic action. One friend described it as the modern equivalent of a cargo cult. At the individual level the test is behavior, as demonstrated by governors caught violating the Covid restrictions that they had insisted it was vital for all to follow.

Nuclear power is the one substitute for fossil fuel that produces no CO2, works whether or not the sun is shining or the wind blowing and can be expanded without limit. Someone who believes that climate change is an existential risk, that almost any cost is worth bearing to prevent it, should be biased in favor of nuclear power, much less likely to oppose it than someone less concerned about climate change. Some environmentalists do indeed support nuclear power3 but most, by casual observation, oppose it.

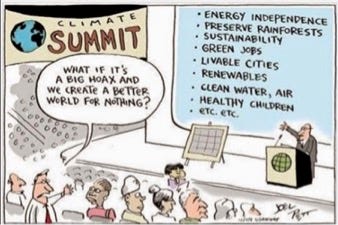

The more general point is demonstrated by a cartoon popular with environmentalists:

By a curious coincidence, the policies needed to prevent climate change were ones the people concerned about climate change, at least the ones who saw that cartoon as convincing, were already in favor of.4

Not everyone who teaches economics qualifies. At one school we visited the only person I could find who appeared to believe in economics told me that he used to teach but was now an administrator.

True, I think, of the Old Testament, but a religious acquaintance informs me that there is an exception somewhere in Paul’s letters.

James Hansen and Stuart Brand are prominent examples.

We have similar concerns.

Yet one thing I notice reading your examples, is that the range of reasonableness we look for is not the same. It overlaps a lot, and both versions rule out the worst of the True Believers (TM). But I'm a bit more tolerant of US-left-flavored positions, and you are somewhat more tolerant of those flavored US-right.

I presume neither of us is quite as driven by truth as we want to be - we're both influenced by other things, perhaps the ideas commonly expressed around us, or our feelings of some people being on our team, and others not.

So if I wanted to spot a right wing True Believer economist, I'd look for one that ignored unpriced externalities, and/or insisted that their effect is negligible, particularly if this insistence were unaccompanied by citations to peer-reviewed research. They can babble about "stakeholders" all they want, and they can even ritually bend the knee to "people not profits", provided they express it in a way that looks like a ritual genuflection. (They get the same exemption I apply to those that credit God for creating whatever it is they are studying, without using some Holy Book as a source of scientific data.)

“By a curious coincidence, the policies needed to prevent climate change were ones the people concerned about climate change, at least the ones who saw that cartoon as convincing, were already in favor of.”

This sentence confused me at first. Encouraging expansion of nuclear power generation is such a needed policy, but generally not supported by the people concerned about climate change. Then I realized that “policies needed to prevent climate change” was not meant literally, but rather that somehow the “policies needed to prevent climate change” were determined under a constraint that these could not include things that offended the orthodoxy, despite any effectiveness. Translation: what they really believe is that nature (and so also society) should be restored to some ideal past, not merely that climate change should be addressed effectively.