The U.S. is richer than it was in the fifties and sixties when I was growing up, so why are there so many more homeless people? I have several possible answers, none entirely satisfactory:

They were there then too, just less visible and with less sympathetic labels: Bums, Tramps.

Such people certainly existed. Although I have been unable to find figures on their numbers — any reader who can is invited to contribute them — I think that if they had been as numerous as the current homeless it would have been obvious. The less sympathetic labels, however, might be part of the answer. The more hostile the society is to a homeless lifestyle, the greater the pressure to avoid it. And it is possible that changed attitudes have moved us from an environment where their numbers were minimized to one where they are exaggerated.

Housing has gotten more expensive. From 1965 to 2023 the median price of a new house sold in the US increased about twenty-fold.1 During that period the CPI increased almost ten-fold, so the real (inflation adjusted) median price of a house roughly doubled. Over that period, however, the average size of a house also roughly doubled, so the cost per square foot stayed about the same.2 Over the same period, median rent increased about 13-fold.3 I don’t have figures for the average size of a rental unit over time but expect it probably increased.

Over the same period the real income of a household at the 20th percentile of the income distribution, the most convenient measure of the income of relatively poor people that I could find, increased by about 50%4 and the size of the average household dropped from 3.7 to 3.13. So it looks as if the cost of housing, per household or per person, has gone up by less than the income of poor Americans. These are very approximate calculations, given the limited data I was able to find online, but they suggest that increased prices of housing are unlikely to be the explanation.

Cheap housing has gotten illegal. In the New York of Damon Runyon’s stories, a decade or two before I was born, single working men or women mostly lived in boarding houses. In the London described in George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, about the same time, men who were poor and unemployed slept in what we would call flophouses, many to a room. The latter arrangement would be illegal in most US cities, the former banned by zoning codes in many parts of US cities, made more expensive by legal restrictions in most.5 That looks like a possible explanation, at least in urban areas.

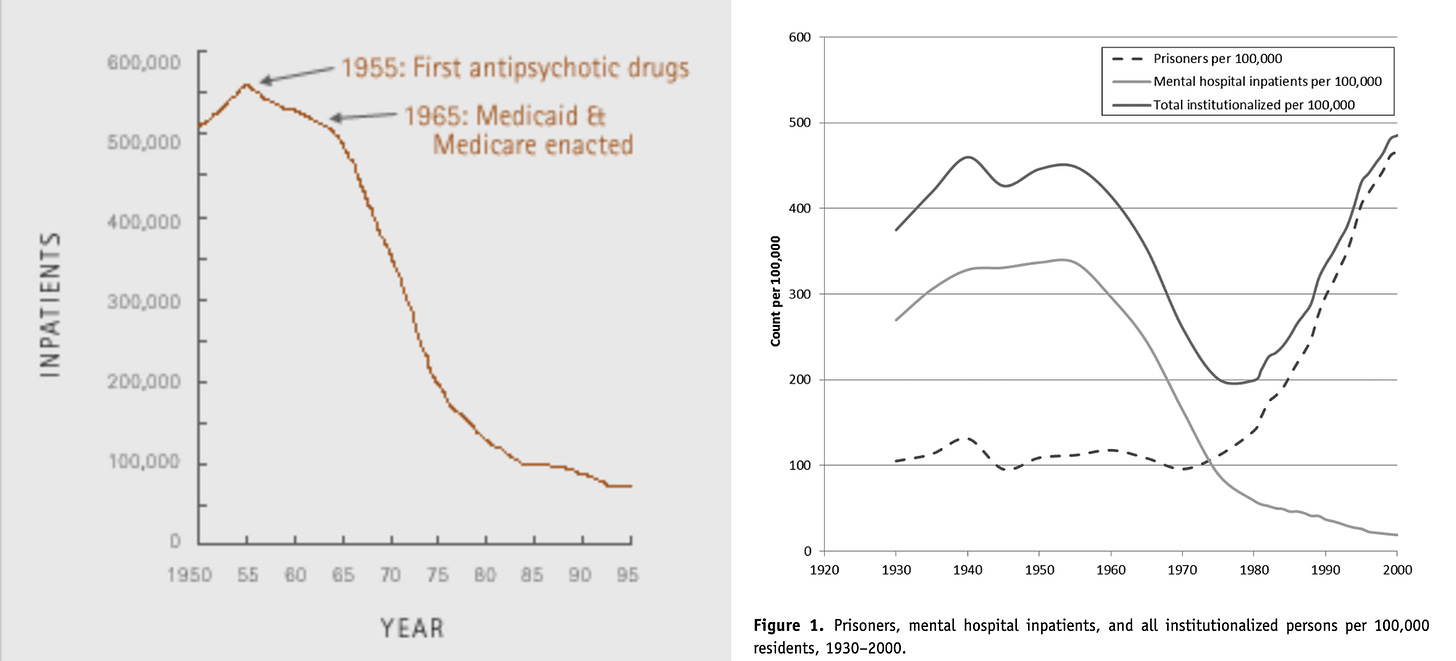

Deinstitutionalization. In 1960 there were about 600,000 patients in hospitals for mental diseases;6 I have not found any figures on how many of them were involuntary commitments. Since 1960 the US population has increased by about 85%; if the institutionalized population increased proportionally it would now be over a million. In 2009, the last year for which the figure is available in the statistical abstracts, psychiatric hospitals had 76,000 beds.7

There are a range of estimates for the number of homeless but all are well under a million, so deinstitutionalization is at least a possible explanation. An alternative explanation of what happened to the population that had been institutionalized, however, is that improvements in psychiatric drugs made it possible for most of those who would in the past have been institutionalized to function successfully outside of mental institutions. Another is that many of those who would, in the past, have been committed ended up instead being arrested and jailed; over the relevant period the prison population has increased by substantially more than a million.8

My arguments so far suggest that possible explanations for the increased number of homeless people are a less hostile legal and social environment than in the past, the reduction by legal restriction in the availability of low cost/low quality housing, and deinstitutionalization. There might be other explanations such as effects of marital breakdown, decreased competence in life skills due to worse child rearing, or things that have not occurred to me but I will stick with those three.

How might we figure out which one or ones are mostly responsible? One way is by where the homeless are. My guess is that red tribe people are less friendly to the homeless than blue tribe people, so the first explanation suggests that they should be mostly in blue tribe cities. The second explanation suggests that there should be more homeless in places that use zoning or other regulation to push out low cost/low quality housing. Here are some relevant figures for both:

In 2020, according to one source, Biden got 60% of urban voters, 50% of suburban. Since the population of most cities includes both, he should have gotten between fifty and sixty percent of the vote in a random city. He did better than that, however, in all of the five cities with the highest percentage of homeless, which provides at least modest support for my first explanation.

An online builder site lists the twenty cities with the most restrictive zoning. Three of the top 5 were among the five cities with the highest homeless rate, providing similar support for my second explanation.

Deinstitutionalization was a national pattern and deinstitutionalized patients can move, so it is hard to contrive a test along geographic lines for that explanation. With enough data for deinstitutionalization and homelessness over time one could compare the patterns, but although I have found data series on deinstitutionalization, shown below, the series I found on homelessness only goes back to 2007,9 more than twenty years after most of the deinstitutionalization had happened. The Wikipedia article on homelessness contains a variety of quotes by different sources at different times,10 but the ambiguity in what the numbers mean — the number who were homeless for at least one night during the year, the number on a single night who were homeless, or long-term homeless — makes it hard to deduce a pattern over time. Perhaps a reader can suggest a source covering the relevant period, about 1955 to the present.

Source for the first graph Source for the second graph

Past posts, sorted by topic

A search bar for past posts and much of my other writing

iProperty management page. I interpolated their 1960 and 1970 figures to get a 1965 figure of about $90.

Table H1 on a US Census site.

I discuss the effect of legal rules on the supply of low-end housing in the context of the nonwaivable implied warrantee of habitability, a court imposed minimum quality of housing regulation, in Chapter 1 of my Law’s Order.

Boarding Houses (Wikipedia).

“Between 1955 and 2013, almost one million SRO [Single Room Occupancy] units were eliminated in the US by regulation, conversion or demolition. … With the huge reductions in the number of SRO rooms available to the lowest-income populations in the US, the role of SROs is being taken over by homeless shelters; however, many homeless people avoid staying at shelters because they find them to be "dangerous and unappealing" or because they do not meet entry requirements (due to being intoxicated), leading to more people sleeping on the streets.

(in New York City) The anti-SRO policies of 1955 were introduced when the demographics of SRO residents changed towards immigrant families; in an environment influenced by "varying degrees of xenophobia and racism", the city took steps to ban new SRO unit construction, prevent families from living in SROs, and change building codes and zoning to discourage SROs. In the 1970s, the city introduced tax incentives for landlords to encourage them to convert SROs into regular apartments, a program which from 1976 to 1981 eliminated two thirds of the SRO stock in the city.” (Single-room occupancy, Wikipedia)

1965 Statistical Abstract, Part 1, Table No. 96.

2012 Statistical Abstract, table 172.

“We also assess the contribution of deinstitutionalization to growth in the U.S. prison population. We find no evidence of transinstitutionalization for any demographic groups for the period 1950–80. However, for the 20-year period 1980–2000, we find significant transinstitutionalization rates for all men and women, with a relatively large transinstitutionalization rate for men in comparison to women and the largest transinstitutionalization rate observed for white men. Our estimates suggest that 4–7 percent of incarceration growth between 1980 and 2000 is attributable to deinstitutionalization.” (“Assessing the Contribution of the Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill to Growth in the U.S. Incarceration Rate,” Steven Raphael and Michael A. Stol, The Journal of Legal Studies , Vol. 42, No. 1)

See also “Deinstitutionalization: A Psychiatric “Titanic.”

Probably because “Since 2007, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development has issued an Annual Homeless Assessment Report, which revealed the number of individuals and families that were homeless, both sheltered and unsheltered.” (Wikipedia)

“the number of homeless people on a given night in January 10: 2023 was more than 650,000 according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development.”

“In 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the homeless population of the country to be 228,621 (or 0.09% of the 248,709,873 enumerated in the 1990 U.S. census) which homelessness advocates criticized as an undercount.”

The number of homeless people grew in the 1980s, nearly doubling from 1984 to 1987.

The chronically homeless population (those with repeated episodes or who have been homeless for long periods) decreased from 175,914 in 2005 to 123,833 in 2007.[272] According to the 2017 AHAR (Annual Homeless Assessment Report) about 553,742 people experienced homelessness, which is a 1% increase from 2016.[273]

c. 1984 “The United States government determined that somewhere between 200,000 and 500,000 Americans were then homeless.”

(All from the same Wikipedia article)

Let me point out the in the rural and smaller (less than 30,000 maybe) suburban communities I am familiar with there are fewer homeless because we care about everyone and work hard to make sure everyone has a place to stay, even if they don't own a house or can afford rent. We treat individuals, not groups, because we know, more or less, the individuals concerned.

We don't virtue signal by putting in place useless but expensive programs that do little to nothing to fix the problem.

I have a former grad student who got her PhD while studying homeless policy. She was fairly liberal, but from a small town in a Blue area. She was appalled to find that she rarely met anyone 'studying' or teaching in homeless policy actually knew real homeless people. "How can they make policy if they aren't familiar with the people they're making policy for?" she asked me. I had to point out they got paid the same either way, and homeless people are "icky." She was quite disappointed.

The homeless are mobile. Wouldn't we expect them to congregate in the places most supportive of homelessness, regardless of what is causing it?