My late friend and colleague Gordon Tullock used to have a collection of graphs of government spending in different countries which showed a clear pattern — expenditure roughly constant for an extended period followed by a period of increasing expenditure, with when the increase started varying by country.1 He showed them to people as a puzzle. I am pretty sure that Gordon’s explanation, either implied or explicit, was that the cause was the introduction of female suffrage. That is the conjecture I will be testing.

I don’t have Gordon’s graphs but Our World In Data has webbed graphs of government expenditure over GDP for a large number of countries as does the IMF.2 This is a Substack post not a research article, so I limited myself to thirteen countries for which the data of female enfranchisement was given in the relevant Wikipedia article. Someone more ambitious could access the much more extensive list of dates for female enfranchisement that I later found and repeat my experiment for a much larger collection of countries.

Looking at the graphs, the pattern Gordon described is there, although less clear than in my memory of what he showed me forty-some years ago; expenditure relative to GDP is reasonably stable for a considerable period than starts to rise, usually with a sharp jump at the beginning. There is also a pattern of expenditure rising sharply for a major war and coming only part of the way down, observed for the UK after WWI and for five countries after WWII. Not counting the wars, about half the countries had two break points during the 20th century, but in each case I was able to distinguish one major one. Readers who wish to evaluate the graphs themselves can do so on Our World In Data.

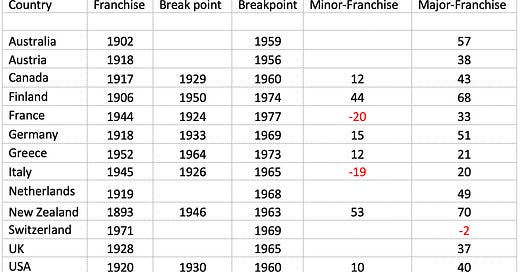

The table shows the date of female enfranchisement, the major break point and any minor break points and how long after (or before) women got the vote the major and minor break points occurred. If the conjecture is correct that last should, for one of the breakpoints, be about the same for all countries, representing the time from women getting the vote to their political influence becoming large enough to show up in expenditure.

The delay between the franchise date and the major breakpoint shows no obvious pattern. For the minor breakpoint, four of the eight countries that have one have a delay of ten to fifteen years. In every case the minor breakpoint occurs before the major, which suggests that the pattern may have existed, imperfectly, in the earlier period but not the latter. I do not know when Tullock drew his graphs but my interaction with him would have occurred when we were colleagues at VPI in the late seventies, so it is possible that the data he was working with predated at least some of the major breakpoints. It would be interesting to repeat my analysis for a much larger collection of countries and see if the results strengthen or weaken the evidence for the conjecture.

A different and more striking feature of the data suggests another explanation for the timing of major breakpoints: All of them are between 1956 and 1977, nine out of thirteen from 1959 to 1970. All of those countries are part of the same political/cultural grouping hence subject to similar political or ideological pressures, which is a plausible explanation for the pattern.

After I started my attempt to reproduce Gordon Tullock’s graphs and test the conjecture I discovered that I was not the first person to look at the question. Lott and Kenny used U.S. state data to see if there was a link between the date of female enfranchisement in the state and state expenditure, and found that:

“Suffrage coincided with immediate increases in state government expenditures and revenue and more liberal voting patterns for federal representatives, and these effects continued growing over time as more women took advantage of the franchise.”3

Suppose It’s True

As readers may suspect from my rather informal efforts above, I am at heart a theorist not an empiricist. The question that intrigues me is not whether the conjecture is true, important as that may be, but what, if it is, are plausible explanations?

The one that occurred to me was the sexual division of labor in developed countries in the twentieth century. A typical pattern for at least the middle classes and above was to have the husband earning income as an employee, farmer, craftsman or the like, the wife running the household. The economic environment with which the husband was familiar was a marketplace. The economic environment the wife was familiar with was a tiny planned society with her as the planner. That would make her more sympathetic to the view of the economy as a larger household controlled by a different but similarly benevolent planner.

An alternative was suggested by a commenter in a comment thread where I had mentioned the issue:

My own suspicion is that it's partly psychological. One of the Big Five personality traits, Agreeableness, is generally reported to average higher in women than in men. I suspect that high Agreeableness and high Openness to Experience go with being progressive, and low Agreeableness and high Openness to Experience go with being libertarian. (I think also of C.S. Lewis's remark that the average man is far more respectful of other people's privacy than the average woman, but the average woman is far more ready to put herself out for other people than the average man.)

Both explanations treat female franchise as a cause of the political change. An alternative possibility, if the data for a larger sample of countries fits the conjecture, is that both were effects of some common cause, perhaps ideological.

P.S. David Henderson points me at a piece by Tullock discussing the observed pattern of government spending but not the differences by country or the possible relevance of the female franchise.

P.P.S. A post by Emil Kirkegaard offers evidence on m/f political differences and the relation of female franchise to government spending, with links to several relevant articles.

Past posts, sorted by topic

A search bar for past posts and much of my other writing

I am working for memory, so do not guarantee that the details are correct. They were probably graphs of spending per capita or relative to GNP.

Both their graph for France and the similar graph webbed by the International Monetary Fund show no increase for World War I, unlike the graphs for Germany, the UK, and the US, and a nearly doubling in about two years in the late seventies, both of which strike me as suspicious. Those two are, however, the only sources I found that cover lots of countries for a sufficiently long period.

Did Women’s Suffrage Change the Size and Scope of Government, John R. Lott, Jr. and Lawrence W. Kenny, JPE 1999, vol. 107, pp. 1163.

This just reminded me of my experience back in 1989-90 I think. A friend and I took a seminar in Montesquieu wirh a quite conservative politial philosophy prof. My friend was/is pretty far Left, and I was/am some weird combination of libertarian/anarchist with traditionalist leanings.

Anyway our entire grade depended on a paper of some 30 pages or so applying what we had learned from the thoughts of Montesquieu and our discussions. And we were both data geeks.

We focused on on the idea that political culture varied according to the average climate of a country.

My friend produced several graphs that demonstrated that the further north of the equator a country was the sooner women got the vote,, AND that the further north of the equator a country was the average consumption of alcohol increased. His conclusion was that the average climate led to heavier drinking in the north, and that drunken men were thus more likely to let women vote.

I used data to show the difference between the honey-production of honeybees versus bumblebees to show that honeybees were Socialists and bumblebees were Capitalists in their production and usage, and that the production depended on the latitude. Closer to the equator, more honeybees and excess honey production. The farther north of the equator more bumblebees that produce just enough honey to keep independent colonies thriving. (Bumblebees do produce honey, but they do not specialize on specific flowers as do individual honeybees, but gather nectar from whatever is available in a harsher climate, and store just enough to start again the next spring.)

That is, the gathering of nectar and the production of honey evolves bees with either Socialistic traits or Capitalist entrepeurnial trait.

Part of my argument was that Socialism tended to fail because it doesn't work well in colder climate countries which were also where capitalism and the industrial revolution started. and are basically still located.

The prof laughed and accused each of us with trying to be funny. (He was right.) But he also gave each of us an A for the actual parts that dealt with philosophy.

I had Gordon write this up for the first edition of my Encyclopedia. He was surprised that I wanted him to because he didn't have a good explanation. I told him that when someone like him is puzzled, it's worth writing up.

Here's the link: https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc1/GovernmentSpending.html